An Art That Speaks for Oneness

I was asked why Post Personalism art sometimes requires an explanation when “art should speak for itself” they say.

The saying “art should speak for itself” carries the implication that those saying it understand the language that the art is speaking. For example, someone who has little understanding of the Abstract Expressionism art movement, will likely have little appreciation of it. Because in order to appreciate abstract art they must possess, to some degree, the visual language required to understand it, and the verbal language that has evolved to discuss it. ‘Visual language’ is an informal way of describing the variety of ways that imagery communicates to us. And ‘verbal language’, has to do with speaking about it technically, such as regarding techniques and art movements.

I was asked why Post Personalism art sometimes requires an explanation when “art should speak for itself” they say.

The saying “art should speak for itself” carries the implication that those saying it understand the language that the art is speaking. For example, someone who has little understanding of the Abstract Expressionism art movement, will likely have little appreciation of it. Because in order to appreciate abstract art they must possess, to some degree, the visual language required to understand it, and the verbal language that has evolved to discuss it. ‘Visual language’ is an informal way of describing the variety of ways that imagery communicates to us. And ‘verbal language’, has to do with speaking about it technically, such as regarding techniques and art movements.

Abstract painting by Jackson Pollock

However, Post Personalism presents an artistic approach for which there is yet little or no language to give it context. Naturally, people encountering Post Personalism art for the first time seek to discuss it using familiar artistic language, which Post Personalism doesn’t fit easily into. Such as discussing it only in terms of its aesthetic merit. Therefore, the saying “art speaks for itself” doesn’t apply precisely to Post Personalism art. It needs the assistance of some verbal description to help give it context.

Context. Vincent Van Gogh's painting "Almond Blossoms". At left shown against a field of red with white dots. At right shown against a tan background. The wrong context can obscure a work of art. An appropriate context can elucidate it.

What then is the context for Post Personalism art? The closest language we have to discussing Post Personalism is a language that, in the art world, is rarely recognized. And that is the language of spirituality. For example, in Post Personalism we ask, among other things, how our artwork explores oneness. Oneness is a word that is used in spiritual traditions such as in Buddhism and Taoism. Beyond that, most people are unable to say much about oneness.

To elaborate on the meaning of oneness, a Zen master might say: “You are one with the universe, but you may not know it. But the fool would say he could not possibly be one with the universe because he is here and the universe is out there.” The oneness that the Zen master is speaking of is one of the founding principles of Post Personalism. So let us for a moment accept the idea, at least hypothetically, that we are already one with the universe. Then, if it were true, would that not change the way we experience everything? If I am one with everything, then I am not only one with you, but also with every undesirable person. I am one with all forms of life and the natural world. I am one with the processes that have brought the world into being.

To elaborate on the meaning of oneness, a Zen master might say: “You are one with the universe, but you may not know it. But the fool would say he could not possibly be one with the universe because he is here and the universe is out there.” The oneness that the Zen master is speaking of is one of the founding principles of Post Personalism. So let us for a moment accept the idea, at least hypothetically, that we are already one with the universe. Then, if it were true, would that not change the way we experience everything? If I am one with everything, then I am not only one with you, but also with every undesirable person. I am one with all forms of life and the natural world. I am one with the processes that have brought the world into being.

Painting of a Zen master

The idea of oneness, as you can see, doesn’t sync well with the way most humans describe their experience, including many artists. We experience fear and opposition to other people who we perceive as threatening and separate from ourselves. There is the belief among humans that everything is separate, not one. You are separate from your neighbor. Races are separate from each other. Genders are separate from each other. Nations are separate from each other. The bacteria in your gut is separate from the blood in your heart. The earth is separate from the sun. Humans are separate from the planet—We think we are on it, not are it. From the point of view of oneness, the artistic creative process is the same creative process that has brought forth this planet and all living things.

An interpretation of the universe

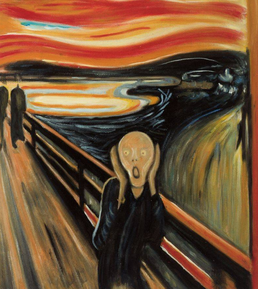

Yes, of course, it is obvious that everything appears separate, but that is arguably a very narrow and selective point of view, and in many cases quite dangerous. And I am not saying that the whole art world and all artists believe that everything is separate. But enough do to make it one of the prominent paradigms in the art world. Separation has become one of the criteria by which we analyze art forms. For example, for over a century Edvard Munch’s “Scream” has been hailed by critics as a masterpiece because it projects the sense of isolation and dread—even horror, that most humans supposedly experience deep in their psyche. But no art critic that I am aware of has ever said that Munch completely missed the mark, for life can be quite pleasant when you learn to get along with it. It is an unexamined assumption that the premise of separation is preferred over oneness. Munch’s “Scream” offers an extreme example; however, other less dramatic examples of separation include a sense of loss, loneliness, tragedy, superiority, inferiority, and cravings for fame and fortune, none of which exist in the state of oneness.

"Scream" by Edvard Munch

If oneness were experienced as a fundamental reality, then it is reasonable to believe that it would produce a seismic shift in the way we understand, participate in, and discuss creativity. That is the entry point for Post Personalism. Post Personalism asks, if we in fact exist in a state of oneness, then how does that inform the way we create? It is not my purpose here to answer that question, as I have already written about it extensively elsewhere. Suffice it to say, the idea of oneness as the foundation for making art has inspired many of my works of art, as well as many fascinating and exciting discussions with colleagues.

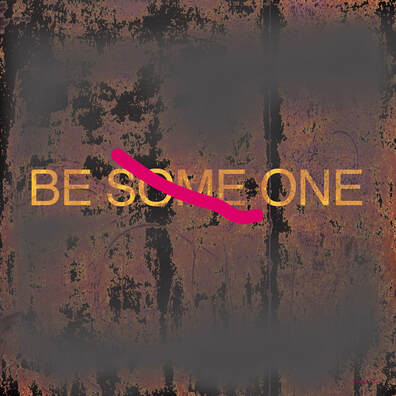

Example of a Post Personalism painting addressing the theme of oneness. By patrick Howe, 2016

And so, it is because of an inadequacy of our use of language that Post Personalism art forms may not necessarily, or immediately “speak for themselves”. Furthermore, I could just as easily take the opposing view and ask why critics, artists, gallerists and art historians are not discussing forms of art in a way that correlates them to the fundamental reality of oneness. Since, if we take the Zen master’s word for it, we—with our art, our symphonies, plays and poems—already exist in a state of universal oneness. So why not talk about it? In Post Personalism, oneness is the root reference for all discussions about creativity. So if a critic were to examine my artwork properly, his or her first question should be “In what manner does this artwork relate to oneness?” The critic’s opinion about the success or failure of the work should hinge on that question. Only secondly should the critic ask how it ‘speaks for itself’ in the conventional way that we use that phrase. However, if we skip the first question and only ask the second, then there is little hope of understanding the deeper meaning of the art.

Whenever I encounter forms of art, whether they be visual, musical, performing or literary, I first ask not how they speak for themselves, but how they speak for oneness. Because I believe that the reality of oneness is a higher and more important context for creativity than the context of aesthetics, or cultural and sociopolitical issues.

Whenever I encounter forms of art, whether they be visual, musical, performing or literary, I first ask not how they speak for themselves, but how they speak for oneness. Because I believe that the reality of oneness is a higher and more important context for creativity than the context of aesthetics, or cultural and sociopolitical issues.